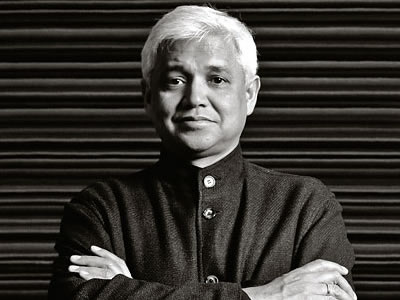

By AMITAV GHOSH

By AMITAV GHOSH

The year I joined College, in 1973, the word among us freshers was that the most terrifying ragger in College lived in Rudra Court, in L9. Terrifying because he wasn’t the usual kind of bullying, bellowing senior.

No, he was to them as the panther is to the elephant, the scimitar to the war club, the rapier to the broadsword. He was bearded, they said, and soft-spoken, so stealthy that you never sensed his presence until he had you square in his sights. No one could actually remember being ragged by him, but everyone knew someone who knew someone…..

In those days, ragging was a serious business: there were nights when we slept in drainpipes around Pandara Park rather than go back to College to face our seniors. It was an atmosphere in which legends battened and grew.

As it happened I succeeded eluding the legend of L9 for a couple of weeks. And then my luck ran out. I was ‘nabbed while attempting to abscond’ as the Indian Express used to say.

“What are your interests fachchey?” growled the legend of L9.

I decided to take a chance: once, while slinking past his door, I had heard a record playing inside.

“I like classical music sir,” I stuttered.

“You do, do you?” he said. “Follow me.”

I was led inexorably into L9; an ancient gramophone was turned on, a record was picked carefully out of a sleeve and placed on the turntable. “Okay miserable fachchey”, he said. “Tell me what this is.”

With the first bars I breathed a sigh of relief. “Emperor Concerto sir”, I said. “Beethoven”.

He paused and then, without giving anything away, he took the record off the turntable and replaced it with another.

I knew this one too; Pastorale, 3rd movement. Another followed; I got it wrong. But I guessed right again with the fourth.

The legend stuck out his hand, “I’m Rukun Advani”, he said. “Let’s go to Maurice Nagar and have a cup of tea.”

Chaiwallas lined the Maurice Nagar bus stop at that time. Some even provided benches. Rukun and I sat talking for hours, while the buses roared past. After that our walks to Maurice Nagar become a night time ritual; something to look forward to through the day. They continued for years (Rukun stayed on in Rudra North for his MA).

As I remember them, the two staples of our conversations were literature and music. My memory is possibly inaccurate in this regard. No matter: in my mind Maurice Nagar will always figure as my own, private Montparnasse.

This friendship, launched so fortuitously in Rudra North, was renewed over and over again in the next few years: in Cambridge, London, Europe, Delhi. Twenty-three years later, Rukun remains one of my closest and most valued friends.

In my second year I lived through this in reverse time, as it were. I was now in L9, having inherited it from Rukun, who’d moved upstairs. One afternoon, walking back to my room, I found a fresher standing on the Rudra Court steps looking, as freshers so often do, like a space alien waiting to be beamed up to his craft.

“Fachchey”, I yelled, “What are you doing standing there like that?”

“I’m looking for the Shakespeare Society sir”, he said.

“You mean Shake Soc.”

“Yes sir”, he said, “Shake Soc sir.”

“Follow me fachchey”, I said. I led him to L9 and made him read out passages from King Lear.

“What’s your name fachchey?”

“Mukul Kesavan sir”, he said.

We became fast friends and have remained so ever since. Mukul was a day scholar so he couldn’t come to Maurice Nagar often. But he did when

he could.

Where is this leading?

Did these friendships have anything to do with my writing? I don’t see how it could be otherwise. Rukun was my first critic; it was because of him that the first piece I ever published saw the light of day. It was he who launched me on what I think of as my Literary Career by finding me a job at the Indian Express. But I couldn’t have taken the job if Mukul and his family hadn’t given me a room to live in.

As far as I am concerned those conversation at Maurice Nagar have never ceased, on or off the page. I find it hugely reassuring that we are all writers now. It is an inescapable fact that all around the world, literary movements have always been sustained by such friendships, by these lifelong conversations, by the kinds of instinctive, almost atavistic loyalty and gratitude that I feel towards Rukun and Mukul (and so many other University friends who, although they have not yet written books of their own, will, I am sure, go on to do so). Literary movements, whether in Calcutta or Vienna, Paris or Rangoon, have always sprung out of these moments, when certain people happen to cross each others’ paths at certain times. There is no explaining why these moments happen when they do; nor should one try. For my part I am just glad that I was present at one.

But does this mean that there is such a thing as a ‘St Stephen’s School of Writing?’ I don’t know. Sometimes I feel we sustained our conversation against (rather than because of) the then prevailing ethos of the College. In any event, I don’t feel that it’s my business to answer this question.

Once on the lawns of Rudra Court I got into an argument with a Philo Soc Type. He won, of course; he won by quoting Wittgenstein, as Philo Soc

Types do.

“Whereof we do not know”, he said, “thereof we should not speak.”

It was the most important lesson I ever learnt on Rudra Court.

[Amitav Ghosh studied History in St. Stephen’s (1973-76), and went on to take a D.Phil. in Social Anthropology from Oxford. He is the highly acclaimed author of The Circle of Reason, The Shadow Lines, In an Antique Land and The Calcutta Chromosome. His latest publication, ‘Countdown‘, a critique of the Indian nuclear tests was published in 1998. Reproduced from here.

Filed under: 1973-74, Delhi, First-hand stories, memory | Tagged: Amitav Ghosh, Mukul Kesavan, ragging in elite colleges, Rukun Advani, St. Stephen's College |

Leave a comment